-

You are currently viewing our forum as a guest, which gives you limited access to view most discussions and access our other features. By joining our free community, you will have access to additional post topics, communicate privately with other members (PM), view blogs, respond to polls, upload content, and access many other special features. Registration is fast, simple and absolutely free, so please join our community today! Just click here to register. You should turn your Ad Blocker off for this site or certain features may not work properly. If you have any problems with the registration process or your account login, please contact us by clicking here.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Why Science is so Hard to Believe

- Thread starter á´…eparted

- Start date

sprinkles

Mojibake

- Joined

- Jul 5, 2012

- Messages

- 2,959

- MBTI Type

- INFJ

It also irks me when people say something is over their head. It is not over your head. If you don't know about it that's fine, just say you don't know. If you don't have the time to learn about it, that's fine too.

But don't paint yourself as stupid because you are most probably not. You are not stupid and knowledge is not magical, it takes work and there's a high probability that you either can't or won't put in the work. And there's nothing wrong with that but I won't accept this "I'm not smart enough" excuse. It's sad.

But don't paint yourself as stupid because you are most probably not. You are not stupid and knowledge is not magical, it takes work and there's a high probability that you either can't or won't put in the work. And there's nothing wrong with that but I won't accept this "I'm not smart enough" excuse. It's sad.

grey_beard

The Typing Tabby

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2014

- Messages

- 1,478

- MBTI Type

- INTJ

- Enneagram

- 5w4

- Instinctual Variant

- sx/sp

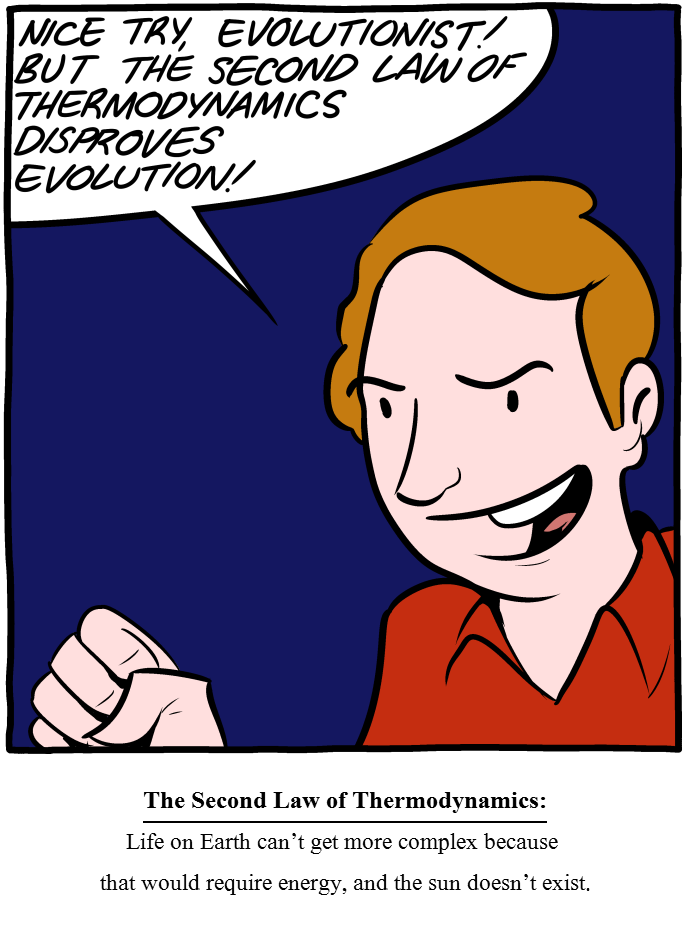

I've heard that excuse. The problem with it is that there are other open systems which would appear to violate thermodynamics by their reasoning - e.g. their refrigerators. Where is the outcry that refrigerators are a lie?

If it's an open system, garden variety thermodynamics does not apply.

Read up on Carnot cycles, OK?

sprinkles

Mojibake

- Joined

- Jul 5, 2012

- Messages

- 2,959

- MBTI Type

- INFJ

If it's an open system, garden variety thermodynamics does not apply.

That was my point. It doesn't matter if they knew whether animals are an open system or not because the reasoning they were using is faulty. And how about you don't patronize me.

Magic Poriferan

^He pronks, too!

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2007

- Messages

- 14,081

- MBTI Type

- Yin

- Enneagram

- One

- Instinctual Variant

- sx/sp

Never heard that one. That's also a problem: people accumulate just enough scientific knowledge to get themselves into trouble. It reminds me a lot of those "freemen-on-the-land" who use as much legal jargon as they can to obfuscate their rationale for not paying taxes, squatting in other people's homes, etc..

EDIT: I decided to satiate my curiosity and google "evolution second law of thermodynamics" to find out precisely how "creation scientists" have determined that evolution violates the second law.

Oh boy.The pseudo-scientific claptrap makes my head hurt. It's more akin to the freemen movement than I thought...

Magic Poriferan

^He pronks, too!

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2007

- Messages

- 14,081

- MBTI Type

- Yin

- Enneagram

- One

- Instinctual Variant

- sx/sp

What does that even mean, aside from "half the people are under the average intelligence of all the people?" It's inherent in the definition of the process, isn't it? Actually, that's not right on my part, it's the median:

Anyway, that's rather a side note. The question I'm left with asking is more this: "Is the scientific process something that can be understood and practiced even by people who are below an IQ100?" [and apparently 2/3 of the population is within 15 points on either side of 100, so... let's say "can people with an IQ85 still practice a scientific process?"] Where's the point where a certain level of intelligence is incapable of understanding the scientifice process of information weighting and evaluation? That could be below the 50% mark, it could be higher than the 50% mark.

I do agree that a major part of the problem is that people are people. I know even wanting to be objective, I regularly have to remind myself to take a step back and reconsider. It's pretty natural for human beings to put together the way "something works" and then treat it as a fixed point on which to build other knowledge, and it can be uncomfortable and/or confusing to constantly look at something you thought was established and say, "Oh, that might not be right, let me reexamine that, then fix EVERYTHING ELSE that it was supporting." But that's the process is: If you come up with new information that doesn't seem to mesh, you explore it further to see if you need to change what you thought you knew or whether it can still mesh with what you thought you knew.

Something this thread reminded me of is that a person with a higher IQ isn't necessarily going to be more reliable here, either. Not only are people with higher educations more polarized, I'll bet people with higher IQs are, too. This is related to correlation between IQ and belief in conspiracy theories and paranormal activity. IQ reflects skills, or a set of mental tools, that you have. There are lots of details about how you use those tools that IQ says nothing about. I've often pointed out (though I've seen no actual study any it's a challenge to think of how to execute such a study) that IQ seems to have little relation to critical thought or lateral thought. It certainly tells us nothing about a propensity for cognitive bias. As such, a person with a high IQ may still not be able to step back from their own beliefs any re-evaluated them, but through their IQ, possess even better means for concocting arguments in favor of what they already believe.

So even saying that people have access to the information but aren't smart enough for it isn't necessarily true. At least, it's not if we go by some of those more rigid, conventional measures of intelligence, like IQ.

sprinkles

Mojibake

- Joined

- Jul 5, 2012

- Messages

- 2,959

- MBTI Type

- INFJ

Something this thread reminded me of is that a person with a higher IQ isn't necessarily going to be more reliable here, either. Not only are people with higher educations more polarized, I'll bet people with higher IQs are, too. This is related to correlation between IQ and belief in conspiracy theories and paranormal activity. IQ reflects skills, or a set of mental tools, that you have. There are lots of details about how you use those tools that IQ says nothing about. I've often pointed out (though I've seen no actual study any it's a challenge to think of how to execute such a study) that IQ seems to have little relation to critical thought or lateral thought. It certainly tells us nothing about a propensity for cognitive bias. As such, a person with a high IQ may still not be able to step back from their own beliefs any re-evaluated them, but through their IQ, possess even better means for concocting arguments in favor of what they already believe.

So even saying that people have access to the information but aren't smart enough for it isn't necessarily true. At least, it's not if we go by some of those more rigid, conventional measures of intelligence, like IQ.

Bill Gaede is a prime example. He's an engineer who worked at AMD and Intel (and stole processor technology and sold it to communists) and the man isn't stupid by any means - he is simply out of his mind.

á´…eparted

passages

- Joined

- Jan 25, 2014

- Messages

- 8,265

This is related to correlation between IQ and belief in conspiracy theories and paranormal activity.

This is a bit off topic, but could you elaborate on this a bit more? For two reasons: A. I have never heard of this before, and B. This sorta makes sense. My mother (who has an IQ of 147, according to her anyway. It doesn't feel right, but considering my own it's likely to be valid), is super into conspiricy theories. Thinks the illuminati are a real thing controling the worlds money in castles in Switzerland, is super anti-vaccine, super anti-gmo, in recent years has paradoxically become anti-climate change, is paranoid about flouride, chem trails, modern medicine, also believes in tarot cards, ghosts, spirits, astrology, and all kinds of other new age beliefs. She's essentially created her own religion. It's boggles my mind how someone who is so intelligent (though in atypical, less show-y ways), is so lost, and so BAD at critical thinking.

sprinkles

Mojibake

- Joined

- Jul 5, 2012

- Messages

- 2,959

- MBTI Type

- INFJ

This is a bit off topic, but could you elaborate on this a bit more? For two reasons: A. I have never heard of this before, and B. This sorta makes sense. My mother (who has an IQ of 147, according to her anyway. It doesn't feel right, but considering my own it's likely to be valid), is super into conspiricy theories. Thinks the illuminati are a real thing controling the worlds money in castles in Switzerland, is super anti-vaccine, super anti-gmo, in recent years has paradoxically become anti-climate change, is paranoid about flouride, chem trails, modern medicine, also believes in tarot cards, ghosts, spirits, astrology, and all kinds of other new age beliefs. She's essentially created her own religion. It's boggles my mind how someone who is so intelligent (though in atypical, less show-y ways), is so lost, and so BAD at critical thinking.

Imagining elaborate stuff takes a form of intelligence.

Critical thinking is a metacognitive skill which is less about intelligence and more about introspective positions. One can be incredibly intelligent - a famous genius - and yet may lack critical thinking in some form or other because they were incidentally directed towards an acceptable bias in such a way that their lack of critical thinking is not entirely apparent. Or in other words, everyone agrees with them. Because they are 'smart.'

Mole

Permabanned

- Joined

- Mar 20, 2008

- Messages

- 20,282

Science is hard to believe because it is counter-intuitive.

By contrast religion is easy to believe because it is intuitive.

And interestingly, what we can perceive with our senses is easy to believe because it is intuitve.

And what we can't perceive with our senses but can only be perceived with telescopes and microscopes and mathematics is hard to believe because it is counter-intuitive.

So the big question is: why for 200,000 years have we been limited to intuitive belief, but only in the last few hundred years have we been able to believe both intuitively and counter-intuitively?

By contrast religion is easy to believe because it is intuitive.

And interestingly, what we can perceive with our senses is easy to believe because it is intuitve.

And what we can't perceive with our senses but can only be perceived with telescopes and microscopes and mathematics is hard to believe because it is counter-intuitive.

So the big question is: why for 200,000 years have we been limited to intuitive belief, but only in the last few hundred years have we been able to believe both intuitively and counter-intuitively?

á´…eparted

passages

- Joined

- Jan 25, 2014

- Messages

- 8,265

For me science is intuitive

Then you haven't taken quantum mechanics. Anyone who says it's intutitive is lying and doesn't actually get any of it.

Pionart

Well-known member

- Joined

- Sep 17, 2014

- Messages

- 4,091

- MBTI Type

- NiFe

So the big question is: why for 200,000 years have we been limited to intuitive belief, but only in the last few hundred years have we been able to believe both intuitively and counter-intuitively?

Some thoughts...

Perhaps most people believe it simply because it is what they are told. I don't think religion is intuitive necessarily but has to be learnt. But the difference is, religion came from someone's intuition originally and was then told, and perhaps fits into the mold of all people's intuition because that is where it came from originally, and science came from the use of an objective methodology. Science has a life of its own, its own intuition. And so we believe now what is told by something that is not human. There is a process we follow, and this process gives us supposed truth. And when you hear about the process, it seems intuitive. Use evidence based methodologies to form conclusions. And the way we express the truth of science is in a form which is intuitive.

Idk

Mole

Permabanned

- Joined

- Mar 20, 2008

- Messages

- 20,282

[MENTION=3325]Mole[/MENTION]

Personally I find that relationship to be inverted. For me science is intuitive and religion counter-intuitive.

Religion projects our natural father into a supernatural loving father called God. This is entirely intuitive.

Science takes us into areas totally outside the experience of our family in the ultra large in Relativity and the ultra small in Quantum Mechanics. Both are counter-intuitive.

What is extraordinary is that it is only in the last few hundred years that some of us have learnt to think counter-intuitively. Why is that?

sprinkles

Mojibake

- Joined

- Jul 5, 2012

- Messages

- 2,959

- MBTI Type

- INFJ

Then you haven't taken quantum mechanics. Anyone who says it's intutitive is lying and doesn't actually get any of it.

Well quantum mechanics isn't intuitive, it's transcendent of our perceived reality. I don't think anyone can be blamed for not quite getting it.

Like field effect transistors. I still don't know WHY they work. I can make one, I know their construction, I know the theory and electron holes and all that stuff but it might as well be voodoo really. But at least I can harness it for predictable effects.

sprinkles

Mojibake

- Joined

- Jul 5, 2012

- Messages

- 2,959

- MBTI Type

- INFJ

I disagree. I never thought God was intuitive.Religion projects our natural father into a supernatural loving father called God. This is entirely intuitive.

Those are both fringe extremes. There's plenty enough to intuit in between in daily experience.Science takes us into areas totally outside the experience of our family in the ultra large in Relativity and the ultra small in Quantum Mechanics. Both are counter-intuitive.

Ideas are memetic. Once the genie is out of the bottle it doesn't like to go back in.What is extraordinary is that it is only in the last few hundred years that some of us have learnt to think counter-intuitively. Why is that?

grey_beard

The Typing Tabby

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2014

- Messages

- 1,478

- MBTI Type

- INTJ

- Enneagram

- 5w4

- Instinctual Variant

- sx/sp

If they knew animals were open systems, they'd know that argument was from thermodynamics was simply inapplicable, which is even worse than merely incorrect. No patronizing intended, sorry for the mistaken impression.That was my point. It doesn't matter if they knew whether animals are an open system or not because the reasoning they were using is faulty. And how about you don't patronize me.

sprinkles

Mojibake

- Joined

- Jul 5, 2012

- Messages

- 2,959

- MBTI Type

- INFJ

If they knew animals were open systems, they'd know that argument was from thermodynamics was simply inapplicable, which is even worse than merely incorrect. No patronizing intended, sorry for the mistaken impression.

Right. Which is why I believe this was no honest mistake.

If they were merely mistaken and didn't know about open systems, they would consistently apply this error, no? They should have said naively that evolution disproves thermodynamics instead of the other way around if this was a simple misunderstanding, because there's tons of other examples if you're not clued in about open systems.

But they didn't consistently apply this mistake, they applied it ONLY where it was convenient, directly, with laser accuracy. Which tells me that it wasn't a simple misunderstanding. I'd say at best it's an extreme confirmation bias, and at worse somebody was intentionally misleading.

grey_beard

The Typing Tabby

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2014

- Messages

- 1,478

- MBTI Type

- INTJ

- Enneagram

- 5w4

- Instinctual Variant

- sx/sp

Then you haven't taken quantum mechanics. Anyone who says it's intutitive is lying and doesn't actually get any of it.

Neils Bohr said the same thing; but recall he was born bred and steeped in classical training; and also that in his day not even the full components of the atom had been sorted out into their proper sizes and mutual relations (plum pudding, anyone?)

In fact, from some of the comments below, a goodly number of the giants *needed* to have someone clamber up and stand on their shoulders:

SCIENCE HOBBYIST: The End of Science

Some thoughts...

Perhaps most people believe it simply because it is what they are told. I don't think religion is intuitive necessarily but has to be learnt. But the difference is, religion came from someone's intuition originally and was then told, and perhaps fits into the mold of all people's intuition because that is where it came from originally, and science came from the use of an objective methodology. Science has a life of its own, its own intuition. And so we believe now what is told by something that is not human. There is a process we follow, and this process gives us supposed truth. And when you hear about the process, it seems intuitive. Use evidence based methodologies to form conclusions. And the way we express the truth of science is in a form which is intuitive.

Idk

Glad to see the IDK at the end. I think your contention is a mixture of conjecture, misunderstanding, and perhaps some mis-classification.

Recall the Cargo Cults spoken of by the late Richard Feynman; and his discussion of psychology...not to mention medicine.

The Cargo Cults saw the planes and landing towers built by Americans in World War 2; they inferred, correctly, by direct observation that the construction of the towers, and the headgear worn by the inhabitants, were correlated with the arrival of the planes bearing hitherto-unseen goods.

So they did their best *imitation* of the towers and radios, but they didn't work; not knowing the underlying mechanism.

Similarly, Feynman spoke slightingly of psychology (hat tip to [MENTION=3325]Mole[/MENTION] for his oft-repeated depredations of MBTI *on a typology forum*

Q. "And what do you say to her?"

A. "I tell her I love her, if that's all right with you!"

Q. (makes notes: third-person auditory hallucinations *confirmed*)

So psychology has the *trappings* of science, but was not able to capture the real experience of being human.

(Even with neuroscience, the mind remains synergistic; and being able to selectively interfere with one function or another cannot recreate a human from scratch.)

And medicine: even dating from the Enlightenment, a reverence for the authority of the past limited advances.

Longer ago, the sacred name of Galen halted inquiry; Semmelweis, after effectively stopping puerperal fever, was condemned to an asylum -- according to Discovery.org, drawing from the US CDC website, he died from an infection he had contracted during an operation; according to Wikipedia, he was beaten and may have suffered gangrene from it; but in any case, his opposition came from practitioners of, *ahem*, science.

Science isn't the only thing which came from objective methodology; engineering and technology did too.

Recall the ancient Greeks: the Golden Ratio, Pythagoras' theorem, ...and Zeno's Paradox. They had objective methodology and reasoning. Contrast that to the Romans, who weren't big on theory, but were great *practical* engineers. As humorist P.J. O'Rourke put it:

The Romans made a better road than anyone ever has since. For a primary road like the Sarn Helen they dug parallel ditches more then eighty feet apart and excavated the soil between them Then they laid in a sand-and-quarry-stone foundation bound on either side by tightly fitted curbs of dressed and wedged stone blocks. On top of this foundation they built an embankment four or five feet high and fifty feet wide, constructed of layers of rammed chalk and flint and finished with a screened-gravel crown two feet thick.

Even so, 1,573 years of neglect have taken their toll. The road has worn down and topsoil has accumulated along it, and the Sarn Helen has turned from an embankment into a ditch. There are washouts and mudholes and boulders in the ditch, too. But the Sarn Helen *is* still there. I doubt we'll be able to say the same about I-95 in the year 3556.

Or, one may consider refinements from the Middle Ages including the Horse Collar and Flying Buttresses: both performed without CAD software or measurement of force vectors.

So advances can and do come without a firm underlying theoretical framework.

And it is possible to have both accurate, and inaccurate intuition; evidence-based methods alone can take you a long way, but they are not sufficient.

Religion projects our natural father into a supernatural loving father called God. This is entirely intuitive.

Science takes us into areas totally outside the experience of our family in the ultra large in Relativity and the ultra small in Quantum Mechanics. Both are counter-intuitive.

What is extraordinary is that it is only in the last few hundred years that some of us have learnt to think counter-intuitively. Why is that?

Not sure that I agree with you about religion being a projection of our natural father: the cultural remnants of Christianity in the modern West give that impression: but the pantheon of classical gods were much more concerned with petty squabbles among themselves, if mythology portrays the beliefs about them accurately.

Buddhism and Hinduism don't seem to have much in the way of a loving Father: and other older religions in both the Old and New world practiced human sacrifice.

As to why some people have learned to think counter-intuitively, I think the answer to that is a combination of several items: increasing technology, in conjunction with greater health (fewer literal plagues due to improved sanitation, Athens was subject to pestilence as much as London) and more food (thanks, Medieval Warm Period!) led to the opportunity for people to do more than live hand-to-mouth intellectually, so to speak.

This was combined with the emergence of a mercantile class, for whom improvements in everything from navigation to transport, led to a great increase in technology, for the direct purposes of acquiring wealth (not to mention that somewhat of Western Civilization had to be built up to the point that there were city-states which were not being attacked constantly, and it was safe to travel from place to place -- The Pax Romana had more benefits than people realized);

the "why" of the ancients (looking for idealized causes, purposes, teleological reasons) became replaced by the "why" of the tinkerer, and thence to the "how" of the engineer; when this was combined with both empiricism *and* the inclusion of mathematical modeling, things really took off.

Cellmold

Wake, See, Sing, Dance

- Joined

- Mar 23, 2012

- Messages

- 6,267

It also irks me when people say something is over their head. It is not over your head. If you don't know about it that's fine, just say you don't know. If you don't have the time to learn about it, that's fine too.

But don't paint yourself as stupid because you are most probably not. You are not stupid and knowledge is not magical, it takes work and there's a high probability that you either can't or won't put in the work. And there's nothing wrong with that but I won't accept this "I'm not smart enough" excuse. It's sad.

I must admit I would rather be called lazy than stupid. Although it might be a bit of one and the other....amongst other 'others'.

This is hitting on something else which might not really be relevant here though. But maybe I can draw it into this so I'm going to try. It's a simple idea: I agree mostly with the notion that people can push past certain self-imposed limits based around intelligence and capability and we all have our traps and our delusions which we've cobbled into these working personalities in order to deal with existing. However I do think there are individual limits which can be hit based on the (assumed real so fuck you Descartes) hardware we have biologically in the form of our brains.

In other words: for some people it really IS over their heads. Otherwise we're just encouraging magical thinking. But then again I love playing all my sides at once if I can remember them, so I can buy that for the average (one day we'll find that right? An average?) person possibly could attempt to put time and effort into researching and studying complex and intricate scientific theories and ideas, but if their equipment isn't quite up to scratch then the amount of time and effort possibly looks negligible for any pay off.

Plus that whole notion of knowledge itself being the reward and there being no end to it. People understand things on different streams and complexities and some are playing with better memory than most of everybody else and some are playing with worse memory.

I think the reason theories like MBTI pop up is because the fast memory tricks a person into thinking they jumped from A to Z and ignored the other 24 letters along the way when really they did it so quickly the other letters were irrelevant. But then you have to pretend that getting distracted by different information, say a number popping up between I & P, is not also part of that process.

I don't know really, but from my basic ( and I mean basic) observations; people get what they're given and then do what they can with it and the only sensible option is to existentially introspect endlessly on what choice is the choice when you made the choice until your hardware ends up at Cambridge in a jar of vinegar.

But that's not fun, so we invent boredom to block out the parts that might be a little bit too much for us...in other words the parts that are "over our heads".

Similar threads

- Replies

- 24

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 34

- Views

- 39K

- Replies

- 16

- Views

- 22K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 11K