EJCC

The Devil of TypoC

- Joined

- Aug 29, 2008

- Messages

- 19,129

- MBTI Type

- ESTJ

- Enneagram

- 1w9

- Instinctual Variant

- sp/so

The Curse of Meh: Why Being Extraordinary Is Not a Matter of Being Universally Liked but of Being Polarizing

by Maria Popova

Published at brainpickings.org

Excerpt:

After spending the entirety of my adult life as a noncitizen immigrant in America, perpetually toiling at the mercy of various visas, I am currently applying for something known as an “extraordinary ability green card†— a document granted to people whose contributions to culture the government deems valuable enough to offer them a slice of the American Dream or, at the very least, to make their lives a little easier by letting them stay in the country and continue to make said contributions with a little more dignity and peace of mind.

...

I’ve become particularly fascinated by the extraordinary part of “extraordinary ability.†At first glance, it implies exceptional, above-and-beyond-the-ordinary ability. But it seems to also mean, rather, the very opposite — extra-ordinary as in possessing an extra helping of ordinary... This would be little more than a personally frustrating curiosity if it only applied to the limited case of “extraordinary ability green card†aspirants — but we also apply this paradoxical understanding of “extraordinary†to just about every aspect of life, from work to life.

Why that happens and how it limits our potential for truly extraordinary lives is one of the many revelatory insights writer, musician, and entrepreneur Christian Rudder explores in Dataclysm: Who We Are (When We Think No One’s Looking) (public library) — a remarkable look at how person-to-person interaction from just about every major online data source of our time reveal human truths “deeper and more varied than anything held by any other private individual,†and how the tension “between the continuity of the human condition and the fracture of the database†actually sheds light on some of humanity’s most immutable mysteries.

Rudder is the co-founder of the dating site OKCupid and the data scientist behind its now-legendary trend analyses, but he is also — as it becomes immediately clear from his elegant writing and wildly cross-disciplinary references — a lover of literature, philosophy, anthropology, and all the other humanities that make us human and that, importantly in this case, enhance and ennoble the hard data with dimensional insight into the richness of the human experience. Rudder writes:

For the reflexively skeptical, Rudder offers assurance by way of his own self-professed “luddite sympathiesâ€:

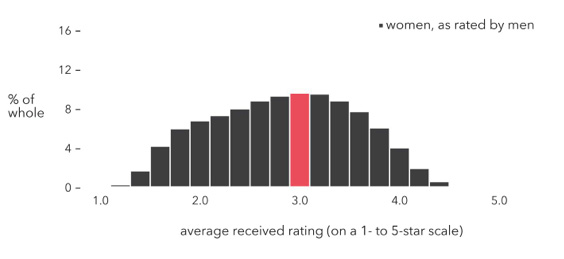

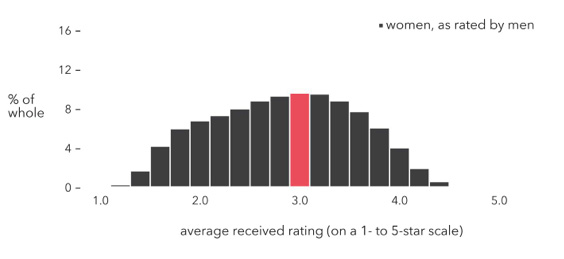

Part of that story is our paradoxical relationship with the notion of the “extraordinary.†Unlike hot-or-not evaluations or Facebook’s unimodal “Like†function, OKCupid asks its users to rank one another based on a five-star rating system. (In one of his many perceptive asides, Rudder notes: “Websites ask you to vote because that vote turns something fluid and idiosyncratic — your opinion — into something they can understand and use.â€) With five points of reference, there are suddenly degrees of opinion, which offer far more depth and dimension than a simple “yesâ€/â€no†rating. To get three stars, it would seem, is to be rated “average.â€

But this is where it gets interesting.

It is a simple mathematical reality that there are two ways of getting an average rating — either most people give you an average rating, or some people rate you really high and others rate you really low, yielding a cumulative middle ground. In mathematics, this concept is known as variance — the more spread out a set of numbers, the greater the variance.

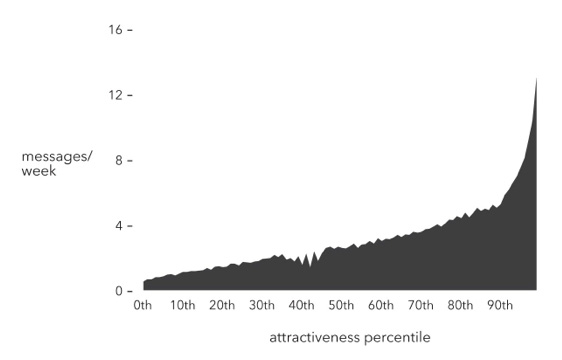

What Rudder and his team found was that not all averages are created equal in terms of actual romantic opportunities — greater variance means greater opportunity. Based on the data on heterosexual females, women who were rated average overall but arrived there via polarizing rankings — lots of 1’s, lots of 5’s — got exponentially more messages (“the precursor to outcomes like in-depth conversations, the exchange of contact information, and eventually in-person meetingsâ€) than women whom most men rated a 3.

Noting that OKCupid doesn’t publish these raw attractiveness scores and so no one’s ratings are being influenced by how others perceive the person being rated, Rudder writes:

...

Indeed, the implications extend far beyond online dating and touch on the broader trap of public opinion. To play to public opinion or seek to please everyone is to aim at precisely that uncontested average, the undisputed and indisputable 3, obtaining which is a matter of being extra-ordinary rather than extraordinary. As soon as you aspire to be truly extraordinary, you begin aiming for those extremes of opinion, the coveted 5’s, and implicitly invite the opposite extremes, the burning 1’s — you make a tacit contract to be polarizing and must bear that cross.

< Read More >

by Maria Popova

Published at brainpickings.org

Excerpt:

After spending the entirety of my adult life as a noncitizen immigrant in America, perpetually toiling at the mercy of various visas, I am currently applying for something known as an “extraordinary ability green card†— a document granted to people whose contributions to culture the government deems valuable enough to offer them a slice of the American Dream or, at the very least, to make their lives a little easier by letting them stay in the country and continue to make said contributions with a little more dignity and peace of mind.

...

I’ve become particularly fascinated by the extraordinary part of “extraordinary ability.†At first glance, it implies exceptional, above-and-beyond-the-ordinary ability. But it seems to also mean, rather, the very opposite — extra-ordinary as in possessing an extra helping of ordinary... This would be little more than a personally frustrating curiosity if it only applied to the limited case of “extraordinary ability green card†aspirants — but we also apply this paradoxical understanding of “extraordinary†to just about every aspect of life, from work to life.

Why that happens and how it limits our potential for truly extraordinary lives is one of the many revelatory insights writer, musician, and entrepreneur Christian Rudder explores in Dataclysm: Who We Are (When We Think No One’s Looking) (public library) — a remarkable look at how person-to-person interaction from just about every major online data source of our time reveal human truths “deeper and more varied than anything held by any other private individual,†and how the tension “between the continuity of the human condition and the fracture of the database†actually sheds light on some of humanity’s most immutable mysteries.

Rudder is the co-founder of the dating site OKCupid and the data scientist behind its now-legendary trend analyses, but he is also — as it becomes immediately clear from his elegant writing and wildly cross-disciplinary references — a lover of literature, philosophy, anthropology, and all the other humanities that make us human and that, importantly in this case, enhance and ennoble the hard data with dimensional insight into the richness of the human experience. Rudder writes:

I don’t come here with more hype or reportage on the data phenomenon. I come with the thing itself: the data, phenomenon stripped away. I come with a large store of the actual information that’s being collected, which luck, work, wheedling, and more luck have put me in the unique position to possess and analyze.

For the reflexively skeptical, Rudder offers assurance by way of his own self-professed “luddite sympathiesâ€:

I’ve never been on an online date in my life and neither have any of the other founders, and if it’s not for you, believe me, I get that. Tech evangelism is one of my least favorite things, and I’m not here to trade my blinking digital beads for anyone’s precious island. I still subscribe to magazines. I get the Times on the weekend. Tweeting embarrasses me. I can’t convince you to use, respect, or “believe in†the Internet or social media any more than you already do—or don’t. By all means, keep right on thinking what you’ve been thinking about the online universe. But if there’s one thing I sincerely hope this book might get you to reconsider, it’s what you think about yourself. Because that’s what this book is really about. OkCupid is just how I arrived at the story.

Part of that story is our paradoxical relationship with the notion of the “extraordinary.†Unlike hot-or-not evaluations or Facebook’s unimodal “Like†function, OKCupid asks its users to rank one another based on a five-star rating system. (In one of his many perceptive asides, Rudder notes: “Websites ask you to vote because that vote turns something fluid and idiosyncratic — your opinion — into something they can understand and use.â€) With five points of reference, there are suddenly degrees of opinion, which offer far more depth and dimension than a simple “yesâ€/â€no†rating. To get three stars, it would seem, is to be rated “average.â€

But this is where it gets interesting.

It is a simple mathematical reality that there are two ways of getting an average rating — either most people give you an average rating, or some people rate you really high and others rate you really low, yielding a cumulative middle ground. In mathematics, this concept is known as variance — the more spread out a set of numbers, the greater the variance.

What Rudder and his team found was that not all averages are created equal in terms of actual romantic opportunities — greater variance means greater opportunity. Based on the data on heterosexual females, women who were rated average overall but arrived there via polarizing rankings — lots of 1’s, lots of 5’s — got exponentially more messages (“the precursor to outcomes like in-depth conversations, the exchange of contact information, and eventually in-person meetingsâ€) than women whom most men rated a 3.

Noting that OKCupid doesn’t publish these raw attractiveness scores and so no one’s ratings are being influenced by how others perceive the person being rated, Rudder writes:

In any group of women who are all equally good-looking, the number of messages they get is highly correlated to the variance: from the pageant queens to the most homely women to the people right in between, the individuals who get the most affection will be the polarizing ones. And the effect isn’t small—being highly polarizing will in fact get you about 70 percent more messages. That means variance allows you to effectively jump several “leagues†up in the dating pecking order— for example, a very low-rated woman (20th percentile) with high variance in her votes gets hit on about as much as a typical woman in the 70th percentile.

[...]

Having haters somehow induces everyone else to want you more. People not liking you somehow brings you more attention entirely on its own.

[...]

Having haters somehow induces everyone else to want you more. People not liking you somehow brings you more attention entirely on its own.

...

Indeed, the implications extend far beyond online dating and touch on the broader trap of public opinion. To play to public opinion or seek to please everyone is to aim at precisely that uncontested average, the undisputed and indisputable 3, obtaining which is a matter of being extra-ordinary rather than extraordinary. As soon as you aspire to be truly extraordinary, you begin aiming for those extremes of opinion, the coveted 5’s, and implicitly invite the opposite extremes, the burning 1’s — you make a tacit contract to be polarizing and must bear that cross.

< Read More >