Article Poster

New member

- Joined

- Mar 4, 2014

- Messages

- 156

- MBTI Type

- ROBO

“Profiles†are the cornerstone of personality type but to the general public, “profiling†is often seen as a despicable practice. In the US, the recent deaths of young black men at the hands of police officers have once again raised questions about whether unfounded assumptions about them contributed to the tragedies. The typical debate—â€Profiling is bad and must stop!†versus “But we’re not profiling!â€â€”has not been particularly productive. Racial and ethnic stereotyping obviously continues despite decades of public condemnation. Maybe*the questions we really need to be considering are more along the lines of: What is profiling? How and when does it lead to bad outcomes? How and when can it be used appropriately?

We need to acknowledge that profiling—extrapolating from minimal information about others to decide how to interact with them—is hardwired into our psyche. It is automatic and necessary. We are constantly required to respond to people and situations before we have much information about them. And it seems likely that in high-pressure, high-risk situations, the ability to make quick judgments (even if based upon defensive paranoia) has evolutionary advantages. Quickly assessing potential threats is a survival skill.

But if profiling is natural and, in many ways, a useful thing, then where exactly does it go awry? The quick assumptions we make about others draw from whatever information we have about them. If we interact with them at length, we can build a profile based on their words, body language, and behavior. I.e., we can guess about the future behavior of an individual based upon the ‘real data’ of observed behavior. But when we have little to go on, we fill in the blanks with generalizations. This is where profiling gets particularly speculative and dangerous, because in the absence of more reliable information, we tend to substitute emotionally charged archetypal abstractions. And the more different from ourselves the person seems, the more likely we are to see them as a threat and interpret their actions in terms of negative archetypal patterns.

C. G. Jung and Isabel Myers were profiling when they wrote about psychological types. And when we type professionals make assumptions about a person, based upon minimal information gathered through a personality assessment tool, we are profiling too. Obviously we type-users view personality profiles as a good thing, providing insights that can benefit both the individual and those who interact with him or her. But if we forget, even for a moment, just how tentative and generalized such a profile is, then we risk doing great harm, just as does a police officer who uses lethal force based on questionable assumptions.

First impressions are hard to overcome. Even though we realize, if we stop to think about it, that our initial conclusions are wildly speculative, we still tend to see subsequent behaviors as fitting and validating that first “profile.†And if that person feels to us like a potential physical threat, or a psychological threat to who we are or to our view of the world, we tend to continue to see them as the enemy.

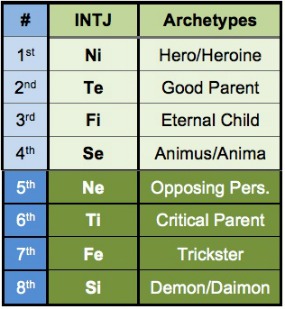

In terms of type, if someone acts from a function-attitude preference that is contradictory to the ego-compatible function-attitudes of our own type, we can easily project our own shadow complexes upon them. For example: If someone activates a function that falls in the fifth position for our type, it can be difficult to see them as anything but oppositional, pushing back at us at every turn for no good reason. That’s because the fifth function often is carried by the oppositional energy that John

Beebe refers to as the Opposing Personality*archetype. (I am an INTJ type; and I confess that my co-editor for this Journal, with her dominant extraverted intuition, frequently elicits this kind of emotional reaction from me.) By the same token, if a person activates our sixth function-attitude—often carried by the Critical Parent—we’ll tend to perceive him or her as dogmatic and stifling. (When I receive feedback on my writing, telling me that I need to more precisely define my point—an introverted thinking concern—I often initially feel that they are trying to crush my creativity.) If someone manifests our seventh—Trickster—function-attitude, they’ll likely seem deceptive to us. (When, with the best of intentions, my dominant extraverted feeling partner tries to support me by giving me what she assumes I need, it often feels to me like she is ignoring what I really need in order to further her personal agenda.) And people who operate from our eighth—Demonic—function-attitude will seem to be attempting to undermine us. (Those who seem inextricably attached to traditional ideas or ways of doing things—an introverted sensing way of operating—can feel to me like they are ignoring reality, with disastrous consequences likely. It’s hard for me not to see climate change deniers, for example, as promoting a great evil—whether intentionally or not.)

We can’t help projecting these associations; but we can avoid acting upon them—especially if we’re aware of them. And even though we form these impressions of others, we can, with conscious effort, remain open to the possibility—the likelihood, really—that we’ve got it at least partly wrong. We can use the archetypal generalizations as the sometimes-useful mental tools that they are, while still holding open the psychological space for the process of getting to know the actual person.

What have been your experiences with the negative side of profiling? How have you been a victim or perpetrator of erroneous generalizations based on race, ethnicity, type, or other differences?

Header Image: Remo Brindisi, Detail from “Tre profili†(“Three Profilesâ€), circa 1975-1980. Courtesy:* Artgate Fondazione Cariplo.

RSS Feed - Link To Personality Type In Depth Article

Last edited: